The Texas Education Agency announced in December 2023 in their paper, Scoring Process for STAAR Constructed Responses, that the constructed response questions in the 2024 STAAR tests will be graded by a hybrid model of human scorers and an automated scoring engine (ASE).

“The Texas hybrid scoring model uses an automated scoring engine to augment the work of human scorers, allowing us to score constructed responses faster and at a lower cost,” TEA said. “The automated scoring engine uses features associated with writing quality and features associated with response meaning. Writing quality features include measures of syntax, grammatical/mechanical correctness, spelling correctness, text complexity, paragraphing quality, and sentence variation and quality.”

With the substantial increase of short and extended response questions (SCRs and ECRs) on the 2024 tests, the use of ASE will save the state $15-20 million dollars that would have been spent on human scorers. The ASE program uses natural language processing, the same technology that many AI programs such as ChatGPT-4 use.

“One very important thing: while there are foundational aspects of the automated scoring engine that could be considered AI, this program is in no way like ChatGPT,” TEA said. “ChatGPT is a generative AI software, the ASE is not.”

This year’s STAAR scoring will go through a five-step process similar to that of previous years, but modified for the addition of the ASE. The process consists of an anchor approval meeting where scoring boundaries are established using sample responses, training both the human and computer scorers, scoring the tests, reporting the scores to districts, and, if necessary, rescoring if there are concerns about whether an SCR score is valid.

“If district personnel or a parent or guardian has concerns about a student’s score on a constructed response question, district testing personnel can request that the student’s response be rescored for a fee,” TEA said in its paper, Scoring Process for STAAR Constructed Responses. “Rescore requests are sent for human scoring. The results of the rescore are provided to district testing personnel. If the score on the constructed-response question changes, the fee is waived.”

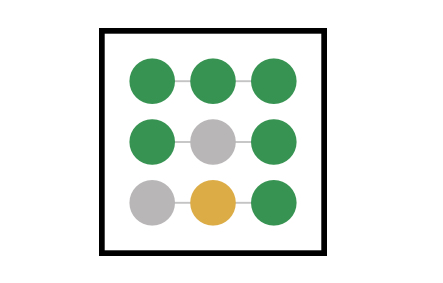

The scoring process involves a “hybrid scoring model” this year, which lets all test scores first be calculated by ASE, and then passes at least 25% of those scores to the trained human scorers for confirmation and to leave room for error. Other than the 25% of constructed responses obligated to go to human scorers, the ASE model will also pass off responses with materials it doesn’t recognize.

“As part of the training process, the ASE calculates confidence values that indicate the degree to which the ASE is confident the score it has assigned matches the score a human would assign,” TEA said. “The ASE also identifies student responses that should receive condition codes.”

Condition codes are given to responses that use too much slang, mostly duplicated text, is off-topic, mostly uses materials the writing prompt, or is too long or short. Additionally, ASE isn’t compatible with languages other than English. Students who take the STAAR in Spanish will be graded solely by humans. There are some doubts as well about this use of AI in grading the STAAR.

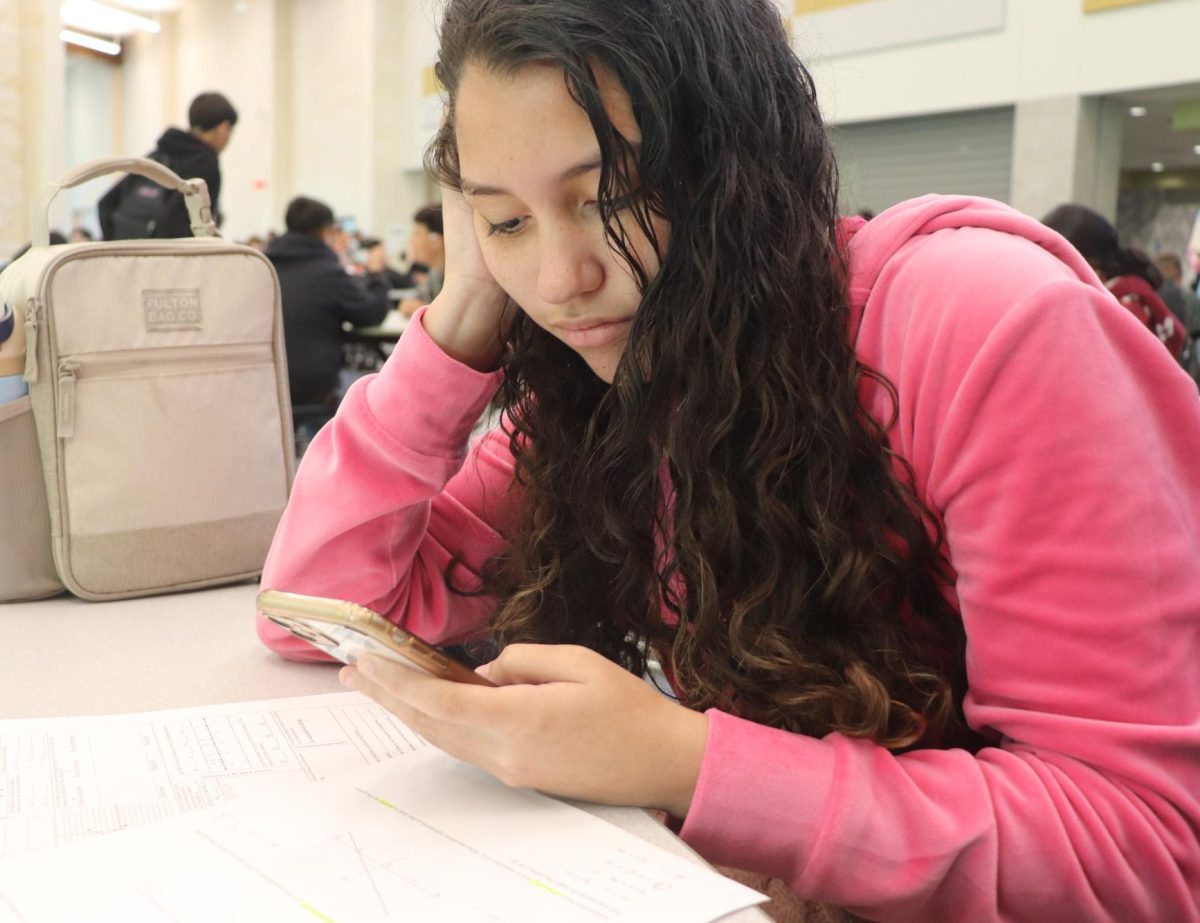

“I don’t think they should use [the program] if they’re not using it for the Spanish speaking students,” Maya Garcia, senior and NEHS officer, said. “That’s really give and take, because the Spanish speaking students wouldn’t have the opportunity to have unbiased opinions if we’re having humans grade their papers.”

Garcia has mixed feelings about the use of AI and computers in the classroom and in grading the constructed responses on the STAAR.

“I feel like it’s good that they’re saving money,” Garcia said. “But also, how much are you really saving besides the money? Are we putting students at risk here for getting more answers wrong than they should be?”

As computer programs and AI are integrated more into the classroom, there have been other concerns as well, both about the reliability of the programs and the ethics of using them in the first place.

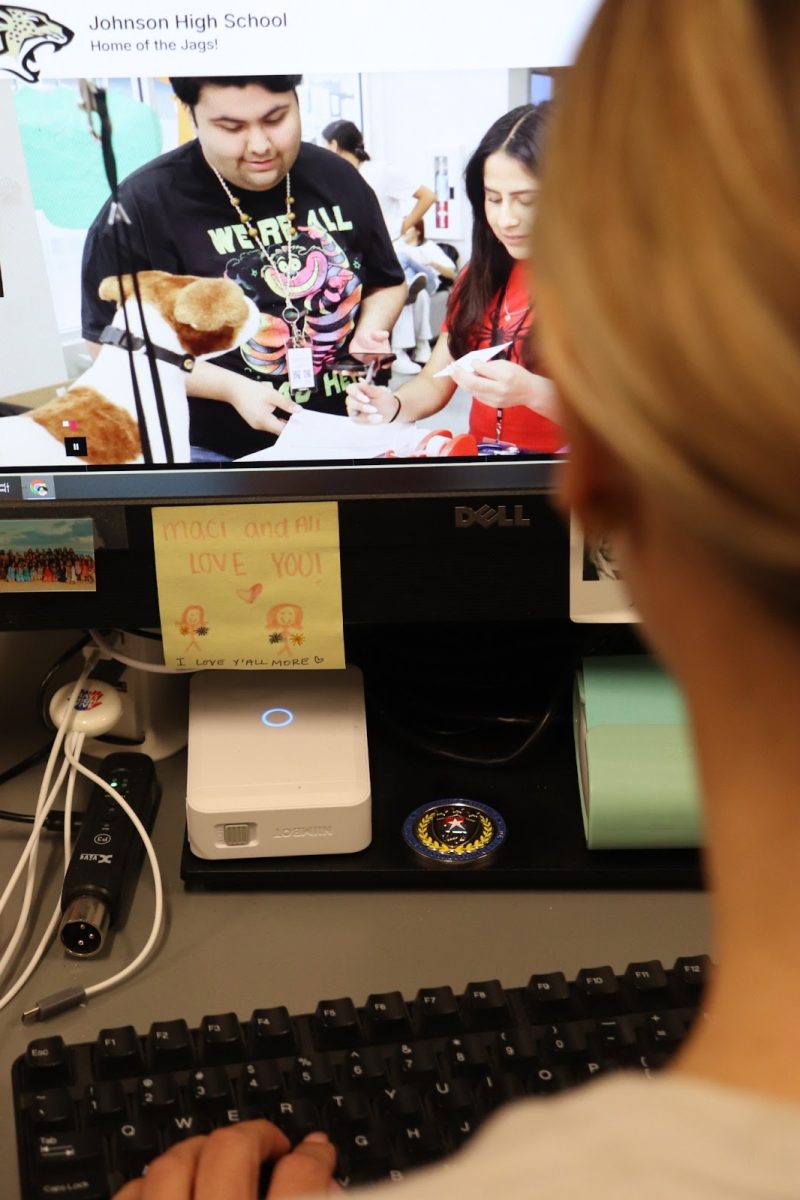

“It depends on how [the system] is being used,” Susan Pope, Johnson ELA teacher, said. “I’ve seen it used before, and it’s fairly accurate, but I don’t think it should replace teachers’ grading because we need to be able to recognize our students’ writing so we know if it’s their writing or if they’re cheating. We need to be able to tell students what we could do to improve their writing, and if we’re not reading the essays ourselves, that’s not very helpful.”

Pope believes computer programs like this one are beneficial when used to help enhance writing and work rather than using it as a substitute for putting in the effort.

“I understand that it’s going to save time, and I know that the programs that are out there are actually pretty accurate,” Pope said. “So as long as they’re going back and making sure to check a sample and check the ones where the computer’s not sure, I think it’s actually a good way to get the scores done faster.”

The $15 to 20 million dollars saved could also potentially be a concern, namely where it goes if not used to pay human scorers.

“I hope that that money goes back to the schools and it’s not just lost somewhere,” Pope said.

“But that to me, that’s money that could go to making sure that schools have the money they need, to make sure there’s enough teachers in schools.”

The TEA assured that the ACE is accurate and fair in its scoring and has plenty of margin for error to detect any problems with the program. In another paper, The State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR®) Hybrid Scoring Study Methods and Results: Spring 2023 Items, published by the TEA, studies were conducted to make sure the ASE could accurately score.

“The study found that the tested Automated Scoring Engine met sufficient performance criteria on each of the field-test programmed and operationally programmed held-out validation samples,” TEA said in the paper. “We expect that the results of the study will generalize to future administrations starting in December 2023.”

Though ASE has been proved to be accurate and largely unbiased, this new use of automated scoring and computer-generated material leaves concerns for the future of computers’ and AI’s role in education.

“I think we really need to watch out,” Pope said. “Students should not be using AI to write their essays because then they’re not learning anything. There are jobs where you need to be able to write something that AI can’t. AI is a useful tool, but it should not be used to replace writing for yourself. So I’m worried about that. I’ve seen a big increase in students trying to cheat by using AI, and they’re really only hurting themselves.”

As computers and AI find new roles in education and, essentially, life, Pope, Garcia and others have some concerns. Pope believes it all comes down to who is using it for what it was designed for and who is abusing it.

“It gets back to ethics,” Pope said. “People who have a personal sense of ethics are not using AI to cheat, they’re using it as a tool. The people who are using it responsibly would use any tool responsibly, while people who are using it to cheat, their sense of ethics is lacking. And that’s something that you can’t really teach in school, it’s something from the home. So it really says more about their upbringing than anything else.”